Banning Offensive language swerving out of control

In today’s culture it is common to hear about or come across campaigns to end words. For example, Spread the Word to End the Word, which according to www.r-word.org is a national campaign to get rid of the word retarded.

Officially starting in 2009 this was the first major campaign to “end a word.” In fact, it played a significant role in the 2010 signing of Rosa’s law, which eliminated the use of the words “retarded” and “retardation” in federal health, education and labor laws.

Although this campaign is noted as well intentioned and backed by hundreds of thousands of passionate supporters, it raises a question: is this the way we should be dealing with language?

Many people, including ourselves, feel that “ending” a word is not the correct solution to such problems, in fact it may be creating a bigger problem that will snowball into a slew of illegal words and phrases.

Words such as “dinosaur” and “birthday” have recently been proposed by the New York City Department of Education as the next candidates to ban. They say that the word dinosaur evokes thoughts of evolution which may be offensive to people who don’t believe in the theory. They also claim the word “birthday” offends groups such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses who do not believe in birthday celebrations.

Now if you just read that and thought something like, “That’s ridiculous!” Or “C’mon.”, you understand my point. I think it’s safe to say there is a line to be drawn between words that need to be addressed and words that need to be tolerated, but the issue spawns in who draws the line.

In some cultures, it is the government who makes those decisions for people and in others it is their religion. But in the U.S. it isn’t either of those things. So for the majority of mainstream United States culture the decision is made by what is deemed popular or acceptable by influential figures in U.S. culture. This evokes another problem: although the popular thing to do is ride the mainstream culture wave, it might not be the best way to solve our inherent offensive language problem.

The fear is that the opinions of the few will begin to outweigh the opinions of the many, and that if we continue to cater to the minority and make political correctness a priority, simple casual encounters will become a mary-go-round of beating around the bush and tip-toeing your way through words or phrases that could be interpreted as “offensive.”

However, some of these campaigns, like the r-word campaign, are legitimate causes with completely valid arguments about words that have almost no meaning other than to slander and demean. But at the same time the word itself may not be the problem, but rather the hate associated with the word. This raises the question: Do you get rid of the word or do you get rid of the hate associated?

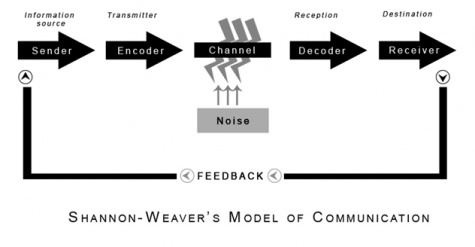

In my opinion, you don’t do either. Getting rid of the hate associated is a good start, but you can’t solve the problem with just that. In order to explain this better I will point to the most basic model of communication, the Shannon and Weaver model of Communication.

In this model, there is a sender and a receiver. The sender has the task of encoding a message (choosing what to say) and the receiver has the task of decoding the message (understanding the meaning). The channel is how the message is presented, whether it be voice communication or writing.

This is important because it demonstrates how a message isn’t just the sender’s responsibility, but rather equal responsibility shared between the sender and the receiver. This is why the proper approach to offensive language isn’t to blame the word sender, but rather both the sender and receiver.

So if someone was going to wear a shirt to school that said “I hate what you believe” on it, then he as a sender has the responsibility of acknowledging that someone is going to disapprove of that shirt. The person who views the shirt has the responsibility of reacting to the shirt by either being offended and confronting the person, or acknowledging the shirt, but understanding that there are people in the world that think differently. This scenario in today’s culture would probably lean towards the option of the shirt being banned and the offended person taking action against the person and the shirt.

Another factor one has to consider is that our culture is in the United States, which operates under the Supreme law of the land in the constitution of the United States of America. In this constitution is the First Amendment right to free speech and expression. So in the scenario above this puts the person in the shirt and the shirt itself in the right. Nowhere in the constitution is the right to not be offended.

the problem isn’t the word, but rather our culture. Nobody likes to be offended, and I’d like to think nobody likes offending people either.